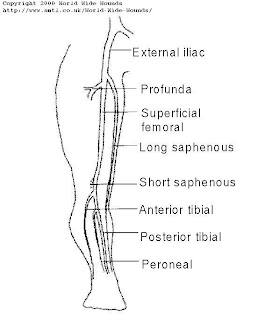

Figure 14: The main veins of the lower limb. The long and short saphenous veins are superficial veins and the remainder are deep veins.

Figure 14: The main veins of the lower limb. The long and short saphenous veins are superficial veins and the remainder are deep veins.

The main reason for scanning these veins is to detect veins in which the valves leak. The leakage may be due to valvular damage or to venous distension [14] . If the valves leak, the veins become incompetent and the blood falls back under gravity as the calf muscles relax, increasing the venous pressure because of the hydrostatic pressure of the column of blood being supported. The condition is known as venous insufficiency. Persistent increased pressure causes superficial veins to dilate producing varicosities, and causing tissue damage distally, showing first as changes in skin colour and progressing to ulceration. The main purpose of treatment is to reduce the excess venous pressure, and this can be done surgically or using bandages. Surgical treatment removes or ties the incompetent veins, and is suitable for superficial vein incompetence since there are other veins which can carry the venous return. The veins are tied at all points where the higher pressure blood from the deep veins enters the superficial system. This is usually at the sapheno-femoral junction or the sapheno-popliteal junction or through incompetent perforators linking the deep and superficial systems. However, the deep veins cannot be removed or tied since they are required to return the blood to the heart. If the deep veins are incompetent, the leg is bandaged to increase the external pressure so that the tissue pressure more closely matches the venous pressure [15] . The applied pressure is graded, being greater at the ankles and decreasing up the leg to encourage the venous return [16] [17] .

The clinical requirement is therefore to identify any superficial incompetent veins and to locate the points where blood is entering from the deep venous system. The presence or absence of deep vein incompetence must also be determined. If there are several incompetent vessels, it can also be useful to indicate which appear to be more significant. A simple examination can be performed using a hand-held continuous wave Doppler unit [18] but this only gives limited information and a full colour duplex scan is preferable. The duplex technique is described in detail by Polak [3]. Patterns of venous reflux have been described by Myers et al [19] and Lees and Lambert [20] , and correlated with clinical symptoms and signs by Labropoulos et al [21] . Further validation of the duplex colour flow examination has been described by Pierik et al [22] .

The examination starts with the patient standing facing the investigator, or lying supine on a couch tilted feet down at least 20� from the horizontal. This is to ensure the veins are filled, and also to ensure that gravity will return blood through any incompetent veins. Coupling gel is put on the probe, which is placed lightly on the skin in the groin over the femoral vein. A light probe pressure is essential, since too great a pressure can narrow or occlude the vein. The femoral vein is identified using the colour Doppler display, and the probe moved along the vein until the site of the sapheno-femoral junction is located (Figure 15). This is near to the point where the femoral vein comes closest to the skin surface. The colour box is placed on the image of the femoral vein just distal to the junction and the thigh is squeezed gently. Flow should be seen in the vein, the colour indicating flow towards the abdomen.The squeeze is then released, and the image inspected for any reverse flow during the release. Any reverse flow persisting for more than one second is normally taken to indicate significant incompetence (ref 3, p 234), although some workers use 0.5 sec [19] or 0.6 sec [20] as the cut-off. The colour box is then placed over the image of the sapheno-femoral junction where the long saphenous vein meets the femoral vein, and the thigh again squeezed and released (Figure 16). Reverse flow persisting for more than 1 sec indicates significant long saphenous vein incompetence.

Figure 15: Longitudinal scan of a sapheno-femoral junction. The superficial long saphenous vein (LSV) joins the deep superficial femoral vein (SFV) to form the deep common femoral vein (CFV)

Figure 15: Longitudinal scan of a sapheno-femoral junction. The superficial long saphenous vein (LSV) joins the deep superficial femoral vein (SFV) to form the deep common femoral vein (CFV)

Figure 16: A normal sapheno-femoral junction on squeeze/release. The blue in the long saphenous vein shows flow towards the heart. The blood velocity waveform shows flow towards the heart as the thigh is squeezed and the flow continues in the same direction as the squeeze is released.

Figure 16: A normal sapheno-femoral junction on squeeze/release. The blue in the long saphenous vein shows flow towards the heart. The blood velocity waveform shows flow towards the heart as the thigh is squeezed and the flow continues in the same direction as the squeeze is released.

Although this procedure can seem straightforward, there are conditions which make the study difficult. The thigh can be difficult to squeeze, and in this case a co-operative patient can perform a Valsalva manoeuvre. The patient breathes in, closes their mouth and nose or throat, and increases the abdominal pressure by trying to force air out against the obstruction. The increased pressure is transmitted to the veins, and reverse flow is seen in the femoral or long saphenous veins if these are incompetent.

Some patients may have recurrent incompetence which has developed since previous surgery. In these cases the long saphenous vein (LSV) may have been ligated and may not communicate directly with the femoral vein. However, small collateral veins may have opened, linking the femoral vein to the more distal LSV, or there may be incompetent perforators linking in the same way (Figure 17). The next part of the study is therefore to identify the long saphenous vein at mid-thigh level and to assess the degree of any incompetence in the same way as before. The probe is placed over the long saphenous vein on the antero-medial aspect of the thigh, posterior to the path of the superficial femoral artery. The calf is squeezed and released, and the presence and approximate duration of any reverse flow is noted (Figure 18). If an incompetent LSV is demonstrated, the vein should be traced proximally up the thigh to identify the source of the incompetence and in particular to look for the sites of incompetent perforators, which can be marked on the skin surface with a crayon.

Figure 17: A large incompetent upper thigh perforator. The large perforator joins the deep superficial femoral vein (SFV) to the superficial long saphenous vein (LSV). On release of a thigh or calf squeeze, blood would flow from the deep vein through the incompetent perforator into the superficial system.

Figure 17: A large incompetent upper thigh perforator. The large perforator joins the deep superficial femoral vein (SFV) to the superficial long saphenous vein (LSV). On release of a thigh or calf squeeze, blood would flow from the deep vein through the incompetent perforator into the superficial system.

Figure 18: An incompetent long saphenous vein. There is normal forward flow on squeezing the lower thigh (SQ), but the flow reverses when the squeeze is released (REL). The reverse flow persists for more than two seconds, indicating significant incompetence.

Figure 18: An incompetent long saphenous vein. There is normal forward flow on squeezing the lower thigh (SQ), but the flow reverses when the squeeze is released (REL). The reverse flow persists for more than two seconds, indicating significant incompetence.

The patient then turns round to face away from the investigator, and relaxes the leg being examined. The probe is placed behind the knee, the popliteal vein and the sapheno-popliteal junction identified and assessed for incompetence by squeezing and releasing the calf. If superficial incompetence is demonstrated, it is important to identify which vein is incompetent. This is usually the short saphenous vein (SSV), but may also be the posterior thigh vein or the gastrocnemius vein.

Having assessed the main deep and superficial veins, it is important to examine any varicose veins to assess how they are being filled. They are usually filled by reverse flow in an incompetent superficial vein (LSV or SSV) but could be filled directly from incompetent perforators. The probe is placed lightly over the varicose vein, which is then traced up the leg using squeeze/release of the calf or thigh to augment flow and aid identification. Reverse flow on release of the squeeze can usually be seen clearly distally, but this may become harder as the probe is moved up the leg. This is because the varicose vein may be fed by small tortuous incompetent veins which pressurize the system but provide restriction to flow. In this case, squeezing the leg distally forces blood up the leg and this dilates the proximal vein providing a reservoir from which the blood falls back on release of the squeeze. However, more proximally the flow reduces because any reservoir is small or non-existent, and it can be impossible to trace the varicose veins satisfactorily. The veins are often tortuous with many branches and it is important to follow the main channel rather than side branches. The only guide is to try to follow the main incompetent vessel.

At this stage of the examination, a clear picture has hopefully emerged, with the incompetent veins identified and a definite source of the incompetence demonstrated. It is very satisfying when this happens, particularly if the picture is complicated. However, there are times when a satisfactory picture does not emerge, and the report has to reflect this.

The final part of the study is to identify any further incompetent perforators, particularly in the calf. It can be difficult to examine the calf with the patient standing on the floor, so some operators stand patients on a stool. Patients do occasionally become faint and very occasionally collapse without warning, so I prefer to examine the calf with the patient sitting up on a couch with the knee bent so that the calf is about midway between horizontal and vertical. The medial, lateral and posterior aspects of the calf are then scanned in longitudinal mode using the colour Doppler display. Incompetent veins can be identified close to the ankle using squeeze/release of the distal calf, and any incompetent veins tracked up to establish any communication with the deep veins. Sites where blood enters the superficial system on release of the squeeze are marked, and the distances from the lateral or medial malleolus are measured and recorded.

Venous examinations, particularly for recurrent incompetence, can be complex and time-consuming. I generally allow 1 hour for a bilateral scan, and 40 minutes for a unilateral study. More time is required if bandages have to be removed before the study. It is important to make notes of the findings at each stage of the study, and a sketch can sometimes be useful as an aide memoire.

http://www.blogger.com/www.worldwidewounds.com/.../Doppler-Imaging.html

No comments:

Post a Comment